Journal: Distributed Log Replication behind AWS

INFO: Japanese version is available in zenn.dev.

Most practical DBMSs implement a write-ahead log (WAL). A WAL is an append-only structure optimized for fast writes, ensuring durability by recording every change to disk before applying it to the main data store such as a B-Tree or LSM-Tree. It is also frequently used for replicating data to other DBMS instances—distributing workloads to reduce latency or replicating data to databases in other regions to improve durability and availability. The significance of the write log is reflected in sayings such as “The truth is the log”1 and “The log is the database”2.

This importance also applies to AWS-managed DBMS services such as Amazon Aurora DSQL and Amazon MemoryDB. Interestingly, these systems delegate the persistence and replication of their write (transaction) logs to a separate component. This internal AWS component, called Journal, supports multi-AZ and multi-region transaction log persistence and replication.

AWS has been building Journal for nearly a decade3. However, official details about Journal itself are scarce, leaving its design and internals largely opaque.

In this article, we delve into the architecture and functionality of Journal, piecing together insights from fragmented AWS technical sources. Through this study, we will also explore broader trends in how large-scale distributed databases are being designed today.

Services Built on Journal

Let’s start by looking at the AWS services built on top of Journal.

Journal supports replication across multiple availability zones (AZs) within a single region, as well as across geographically distributed regions. As will be discussed later, Journal employs different replication methods depending on the placement of replicas. For convenience, this article refers to these as multi-AZ Journal and multi-region Journal, respectively.

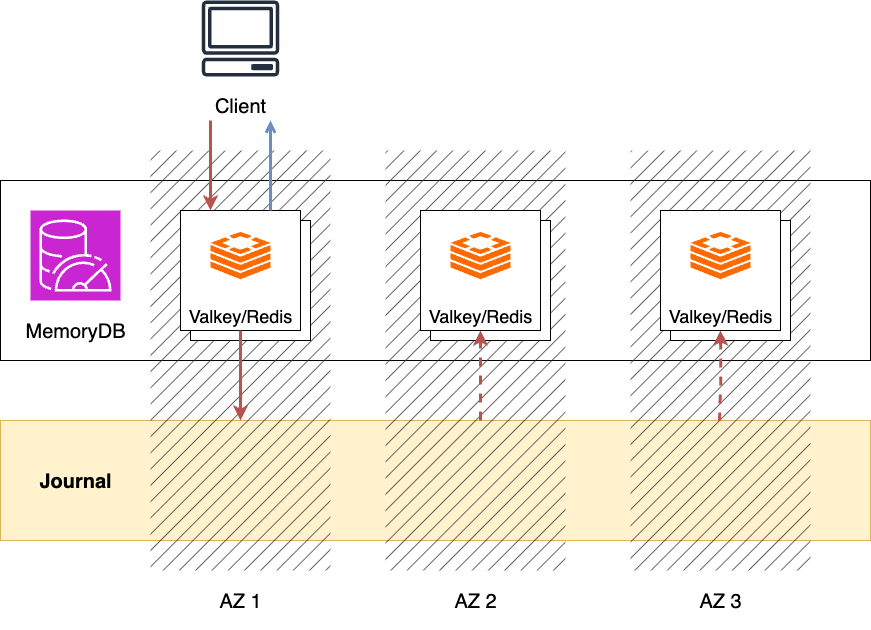

Amazon MemoryDB

Amazon MemoryDB is an in-memory database compatible with Valkey/Redis. With data written to MemoryDB being immediately persisted, it offers high availability and fault tolerance.

This persistence is achieved through the multi-AZ Journal456. After applying writes to the Valkey/Redis shard7, MemoryDB synchronously commits the transaction to Journal and then responds to the client with success. This provides durability at the multi-AZ level.

The transactions recorded in Journal are used for asynchronous replication to secondary nodes and for periodic snapshot creation for data recovery. Also, leader election among replicas is implemented using Journal’s conditional append API and leases.

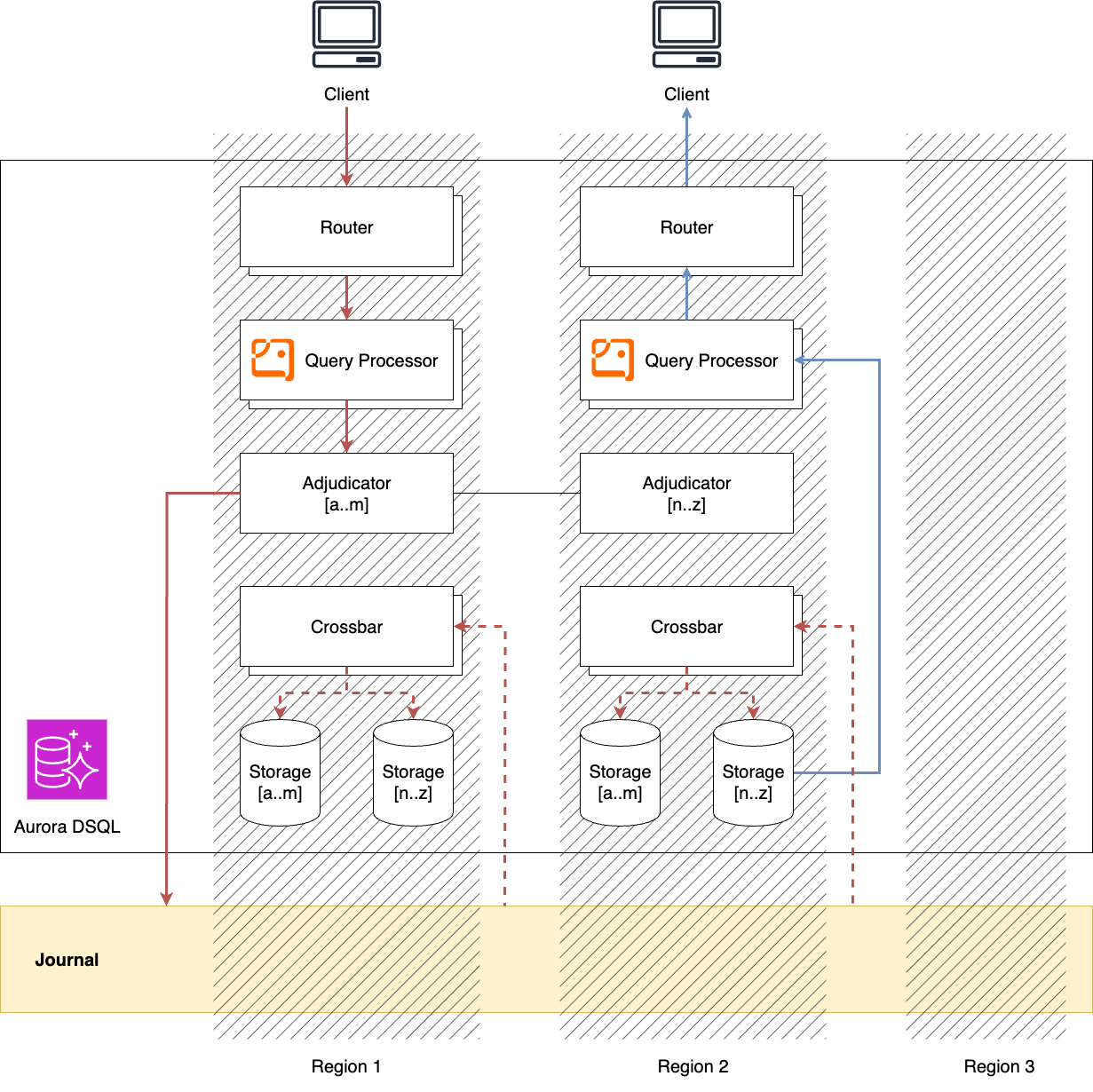

Amazon Aurora DSQL

Amazon Aurora DSQL is a PostgreSQL-compatible, serverless, distributed SQL database. In DSQL, replicas deployed across multiple AZs or regions maintain a complete copy of the data, and clients can read from and write to the replica within their own AZ or region (active–active).

In DSQL, WAL persistence and replication across AZs and regions are handled by Journal8.

During a write operation, a transaction processed by Query Processor is checked for conflicts by Adjudicator.

If no conflicts are found, the transaction is committed to Journal.

Once the commit is completed, the client is notified of its success.

In parallel, the Storage component retrieves the committed transaction via Crossbar and updates its local view.

Cross-AZ or cross-region latency is incurred only during COMMIT—that is, when Journal commits the transaction to multiple AZs or regions.

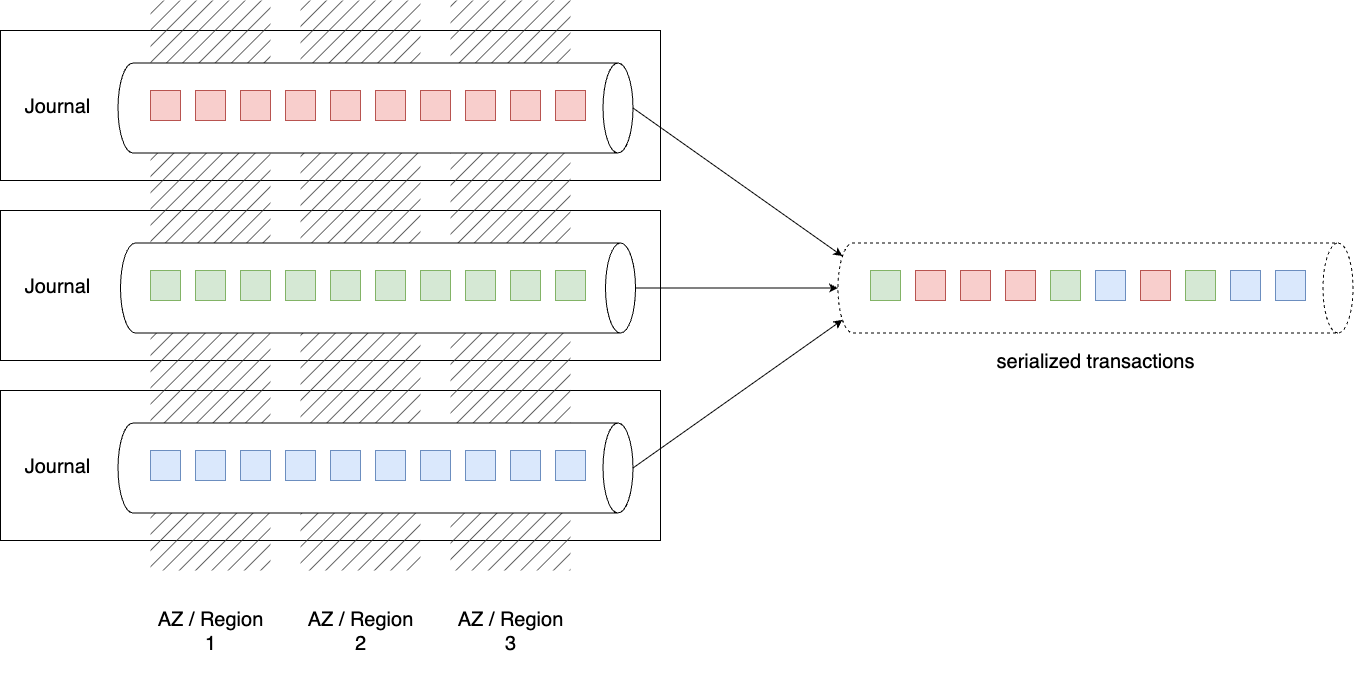

Journal orders committed transactions by their timestamps. Since a transaction can target any range of keys, the transaction log in Journal is not partitioned by key space. Therefore, each horizontally scaled Journal instance stores and orders transactions individually. It is the responsibility of DSQL (specifically, the Crossbar) to retrieve transactions from all Journal instances and establish a total order.

Reads operate against a snapshot of the database as of the transaction’s start time $t_\mathrm{start}$ (snapshot isolation). This is implemented using MVCC and is handled entirely within the local Storage. Storage retrieves and applies all transactions from Journal up to $t_\mathrm{start}$ before serving the read. This design allows reads to proceed without coordination like locks or leader-election, ensuring they do not block other reads or write transactions.

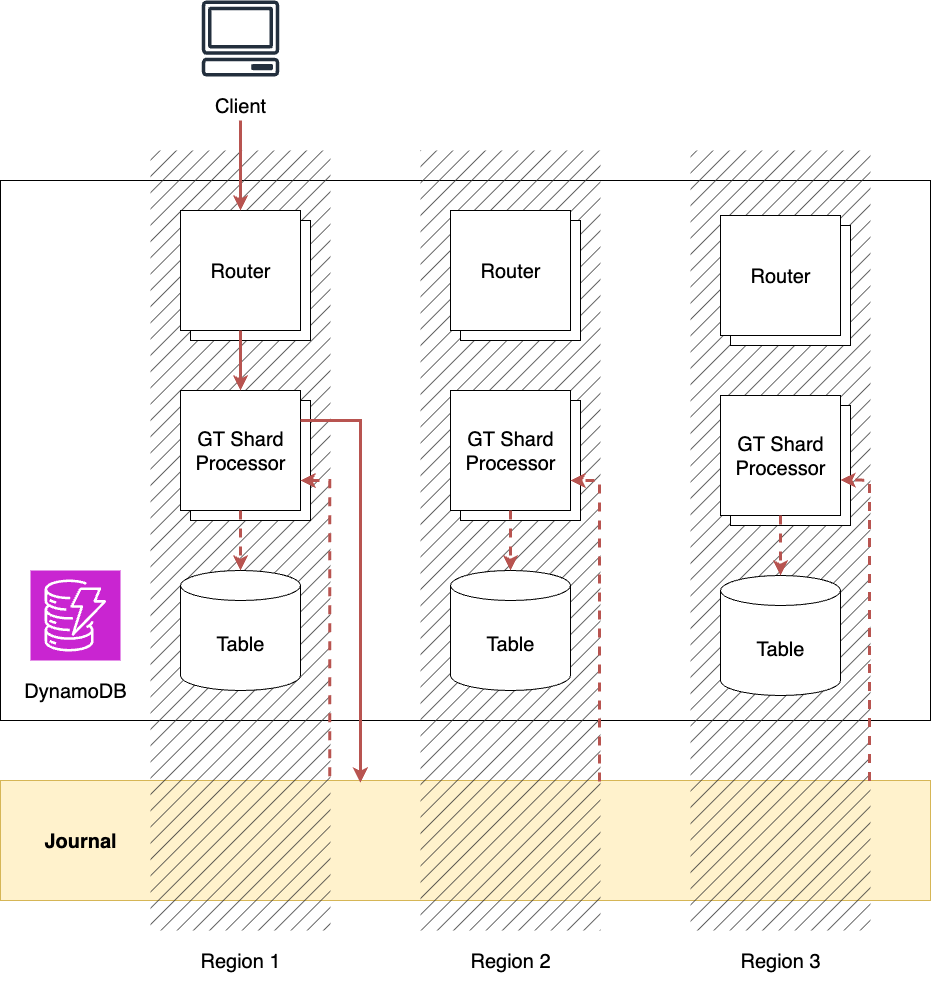

Amazon DynamoDB global tables

Amazon DynamoDB is a serverless NoSQL database service. Amazon DynamoDB global tables replicate tables across multiple regions, allowing reads and writes in each region (multi-active).

Since June 2025, DynamoDB global tables supports strong consistency across multiple regions9. This ensures that clients always read the most up-to-date data, regardless of the region they access.

Inter-region replication for DynamoDB global tables is implemented using multi-region Journal. Writes to a table in one region are first committed to Journal, and once the commit succeeds, the client is notified. DynamoDB tables in other regions share the same Journal transaction log; upon receiving the committed write, they apply it locally as well. Journal accepts and orders writes from multiple regions, ensuring data consistency.

When reading data from a region, the local DynamoDB table may not yet reflect writes made in other regions. To guarantee strong consistency, GT Shard Processor handling the request commits a special record called heartbeat to Journal at read time. By retrieving its own heartbeat from Journal, it can ensure that all writes committed up to the heartbeat’s commit time have been applied locally, allowing it to return the most current values.

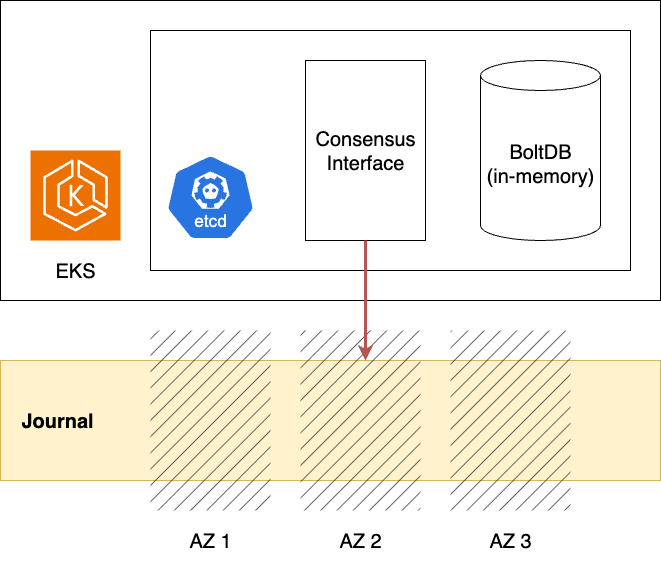

Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service

Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS) is a service that provides managed Kubernetes clusters.

Typically, Kubernetes clusters store objects in etcd, which relies on the Raft consensus algorithm to ensure consistency.

EKS replaces this Raft-based consensus with multi-AZ Journal10. This enables scaling out the etcd cluster beyond the limits imposed by quorum. Furthermore, since Journal guarantees AZ-level durability, the etcd key-value store (Bolt) can store data in memory (tmpfs), achieving high read/write throughput and stable latency.

Why Use Journal

So far, we’ve seen how various AWS DBMS services rely on Journal. But why do these services delegate transaction persistence and replication to Journal? There appear to be two main reasons.

The first is to keep the implementation of DBMS services simple. Achieving consistent reads and writes through data replication requires significant design and engineering effort, regardless of the approach. By centralizing replication responsibilities in Journal, each DBMS service can avoid implementing these mechanisms individually, achieving a clear separation of concerns.

The second reason is to enable flexible scaling of DBMS services. By offloading persistence and replication to Journal, each DBMS component can scale independently based on workload. For example, MemoryDB can scale its in-memory engine (Valkey/Redis) based on DRAM usage, while scaling Journal based on write bandwidth. Similarly, DSQL can scale components such as the Query Processor (Firecracker MicroVMs), Adjudicator, Crossbar, and Storage independently according to their resource usage.

This approach of separating components and their associated hardware resources to enable flexible expansion is called disaggregation11, and it has become an important trend in modern DBMS design12.

Design of Journal

Journal seems to provide a simple API that supports appending and subscribing to transactions. Its required features and architectural characteristics include:

- Transaction serialization: Each transaction appended to Journal must be assigned a unique sequence number. All clients subscribing to Journal must be able to receive transactions in the same order.

- Conditional transaction appends: Journal must support conditional appends, similar to compare-and-set operations, where new data is appended only if certain conditions are met (e.g., based on a specified committed transaction).

- Scalability: Journal must be able to scale in or out flexibly to accommodate varying write bandwidth requirements.

- Durability: Data must be recoverable from replicated copies even if some AZs or regions experience data loss.

- Availability: Clients must be able to perform append and subscribe operations even if some AZs or regions fail.

- Performance: Since committing to Journal lies on the critical path of database read/write operations, its latency must be low enough to avoid impacting service reliability.

Some of these features and characteristics involve trade-offs. The following sections explore how Journal achieves them.

Serialization and Scalability

To prevent commits to Journal from becoming a bottleneck, it is necessary to scale out Journal according to write throughput.

At the same time, transactions appended to Journal must be serialized to ensure data consistency. A naive approach would be to allow writes only from a leader elected via Multi-Paxos or Raft, but this limits the benefits of scaling out. In addition, the DSQL example shows that the Journal transaction log may not be partitioned by key space.

Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that each scaled-out Journal instance maintains its own transaction log. In fact, DSQL’s Crossbar can be viewed as a component that merges the transaction logs from each Journal instance into a single log with a total order. The question then arises: how is the global total order of transactions determined?

The key lies in the fact that transactions appended to the log are ordered by timestamps13. AWS machines provide microsecond-level clock accuracy, so even transactions committed on different Journal instances can usually be strictly ordered. In the rare case of timestamp collisions, strategies such as detection by a component like DSQL’s Adjudicator, or assigning priority to the originating client or Journal instance to break ties, can be employed.

This also highlights that, for hyperscalers like AWS, precise time synchronization across nodes is a foundational element of database design. It is well known that Google Spanner relies on TrueTime for bounded-time uncertainty. Meta, on the other hand, has deployed hardware and software in its data centers to achieve time synchronization with 99.9999% confidence and less than 500-nanosecond error, using it for commit-wait to guarantee linearizability of reads and writes.

Durability and Availability

To ensure durability, Journal replicates transactions to three AZs or regions. To maintain availability, Journal should not wait for all replicas to complete writes; instead, it should consider a commit successful once a sufficient number of replicas have persisted the data.

To meet this requirement, Journal employs different replication protocols depending on the replica placement14:

- multi-AZ: a variant of Chain Replication (controller is Paxos-based)

- multi-region: quorum-based

We will discuss the individual protocols in detail later. What is noteworthy here is that Journal does not rely on leader-based consensus algorithms such as Raft or Multi-Paxos for replication.

While leader-based consensus algorithms simplify replication, they are not always optimal15:

- Durability and storage efficiency: Suppose we want to tolerate failures of $f$ replicas. Raft and similar consensus algorithms require $2f+1$ replicas, whereas Chain Replication only requires $f+1$.

- Availability: If a replica goes down, Raft or Multi-Paxos may stall commits if the downed node is the leader. In contrast, quorum-based approaches can continue committing as long as the quorum is met, regardless of which node fails.

This demonstrates that Journal selects the most suitable replication method depending on the replica placement. The next section looks at the replication strategies for multi-AZ and multi-region configurations in detail.

Multi-AZ Replication

Journal uses a variant of Chain Replication16 for multi-AZ replication. Chain Replication is a protocol in which data is transferred from node to node in a “bucket brigade” fashion, with reads served only from the tail node. Known variants include CRAQ17, used in the distributed file system 3FS developed by DeepSeek18, but the exact protocol employed by Journal has not been disclosed.

The controller plane uses Paxos. Since basic Chain Replication does not support adding or removing nodes from a replication group, such management operations (reconfiguration) are likely handled by the consensus algorithm.

This design is similar to Virtual Consensus1920 in Delos, where state machine replication uses a virtual log composed of multiple loglets. Appends are made to the tail loglet, but there is no need for the consensus algorithm to provide fault tolerance at this stage.

Multi-Region Replication

Journal uses a quorum approach for multi-region replication. With support for three regions, a transaction is considered committed once writes to any two regions have completed. Reads are also performed from at least two regions.

However, quorum alone does not guarantee linearizability21. Consider a write replicated to regions A, B, and C. Once the write to region A completes, a client reading from regions A and B will see the new data. But if that client immediately reads from regions B and C, the same data may not be visible yet.

To prevent such anomalies, Journal’s read path probably relies on AWS’s precise time synchronization.

Another noteworthy aspect of Journal’s multi-region replication is its replication topology. Suppose a Journal client in region A writes a transaction to regions A, B, and C. If a network partition occurs between regions A and B, the client or replica in region A will be unable to complete the write to region B. In this case, the replica in region C can forward the data to region B, completing the write on behalf of them22.

Conditional Append

Journal supports conditional append operations. In MemoryDB, this is used to elect a primary (leader) among replicas and to restrict writes to that leader.

A conditional append specifies the sequence number of an already committed transaction when issuing a write, and commits the new transaction only if certain conditions are met. It is also described as an API for atomically updating specific values, such as the current leader information.

The interface and implementation details of this feature have not been disclosed. Theoretically, since Journal can be regarded as a system providing total order broadcast (also known as atomic broadcast), it could support linearizable compare-and-set operations on top of it23.

For example, in a leader election, each node could maintain the current leader information in a virtual storage space on the log and attempt promotion to leader as follows:

- Node

ncommits a leader election request{"leader" : n}to the log. - Node

nretrieves the next committed leader election request{"leader" : l}from the log.- If

l == n, nodenbecomes the leader (leaderis set ton). - If

l != n, another node has already been elected leader (leaderremainsl).

- If

In practice, storing a lease (expiration time) together with the leader information helps stabilize the system by fixing leadership to a single node. The leader periodically renews the lease to maintain its role, while other nodes attempt promotion only if the lease is not renewed within a certain time window.

Verification of Journal

Journal is the component responsible for durability and replication. Given its nature, verifying the correctness of the system is critically important.

Journal’s specifications have been formally verified using TLA+24. Also, AWS has developed Must, a Rust-based framework for verifying distributed systems25, and Journal has been verified with Must as one of its benchmark cases. More broadly, AWS applies rigorous correctness checks to core services such as S3 and IAM, employing techniques like formal methods and automated reasoning.

Related Work

Several middleware systems such as Apache ZooKeeper, etcd, and Google’s Chubby26 centrally and consistently manage replicated data using consensus algorithms. A key difference from Journal is that they provide a key-value store rather than a log-structured data store. They are not well-suited for handling massive datasets or high-frequency writes, and are primarily used to maintain service configuration and metadata.

If we think of Journal as a log-append and distribution service, we can also find similarities with message brokers like Apache Kafka and RabbitMQ. Unlike Journal, however, these services typically lack strict ordering consistency or exactly-once semantics for message delivery.

Journal can be seen as an example of the Shared Log Abstraction2728–a design principle that isolates the log into its own component (or layer), separate from databases or other distributed systems. This decoupling allows the database to offload complex replication and consensus logic, enabling independent scalability. Middleware such as Corfu and LogDevice follow this pattern.

Notably, LogDevice, developed by Meta since 2017, has supported the company’s production workloads. Like AWS’s Journal, it provides availability, durability, and serialization of appended records for use cases such as transaction logs, WAL storage, and event streaming. Unlike Journal, however, LogDevice uses a dedicated Sequencer node for record ordering and a variant of flexible Multi-Paxos for reads and writes.

Conclusion

In this article, we introduced Journal, an internal component developed and used by AWS as the foundation for many of its DBMS services. We also explored how Journal is designed, based on publicly available technical materials from AWS.

There are still aspects of Journal’s design that remain unknown. In particular, there appears to be no public information on how it achieves the performance required of a DBMS WAL or how it discards transaction logs that are no longer needed. It would be nice if more details on these parts were revealed in the future.

Our exploration of Journal also touched on techniques that are becoming mainstream in modern large-scale distributed databases–such as precise clock synchronization between nodes, disaggregation, and selective use of consensus algorithms.

These approaches are, in part, enabled by hyperscalers with the ability to build massive data centers and procure hardware at scale. As the ecosystem evolves, however, they may well find broader adoption beyond the hyperscaler world.

Pat Helland. 2015. Immutability changes everything. Commun. ACM 59, 1 (January 2016), 64–70. (doi) ↩︎

Alexandre Verbitski, Anurag Gupta, Debanjan Saha, Murali Brahmadesam, Kamal Gupta, Raman Mittal, Sailesh Krishnamurthy, Sandor Maurice, Tengiz Kharatishvili, and Xiaofeng Bao. 2017. Amazon Aurora: Design Considerations for High Throughput Cloud-Native Relational Databases. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD ‘17). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1041–1052. (doi), (amazon.science) ↩︎

“Journal is an internal component we’ve been building at AWS for nearly a decade, optimized for ordered data replication across hosts, AZs, and regions.” – DSQL Vignette: Transactions and Durability - Marc’s Blog ↩︎

Yacine Taleb, Kevin McGehee, Nan Yan, Shawn Wang, Stefan C. Müller, and Allen Samuels. 2024. Amazon MemoryDB: A Fast and Durable Memory-First Cloud Database. In Companion of the 2024 International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD ‘24). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 309–320. (doi), (amazon.science) ↩︎

For technical details on MemoryDB, see the paper, as well as explanatory articles by Murat Demirbas (Amazon MemoryDB: A Fast and Durable Memory-First Cloud Database) and Marc Brooker (MemoryDB: Speed, Durability, and Composition). ↩︎

In the MemoryDB paper, the component referred to as the “transaction log service” is in fact Journal, as explicitly confirmed by Marc Brooker. ↩︎

This behavior is better described as write-behind rather than a write-ahead log. Valkey/Redis replication is normally asynchronous, occurring after database writes. MemoryDB replaces this step with Journal, allowing Valkey/Redis to be used with minimal changes while still replicating non-deterministic operations like SPOP. ↩︎

Formal technical papers on DSQL have not yet been published. For this article, reference was made to Marc Brooker’s DSQL Vignette series (1, 2, 3, 4), the AWS re:Invent 2024 talk, explanatory articles by Marc Bowes (Amazon Aurora DSQL), and a development story by Werner Vogels, Amazon CTO (Just make it scale: An Aurora DSQL story). ↩︎

See the AWS re:Invent 2024 talk by Jeff Duffy and Somu Perianayagam, especially from 32:17 onward. ↩︎

For the EKS improvements discussed here, see Under the hood: Amazon EKS ultra scale clusters. ↩︎

Jianguo Wang and Qizhen Zhang. 2023. Disaggregated Database Systems. In Companion of the 2023 International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD ‘23). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 37–44. (doi), (slides) ↩︎

“Storage-compute disaggregation in databases has emerged as a pivotal architecture in cloud environments, as evidenced by Amazon (Aurora), Microsoft (Socrates), Google (AlloyDB), Alibaba (PolarDB), and Huawei (Taurus).” – Understanding the Performance Implications of Storage-Disaggregated Databases ↩︎

“Each journal is ordered by transaction time” – Just make it scale: An Aurora DSQL story ↩︎

“In-region replication is a chain replication variant (with a Paxos-based control plane), cross-region is a custom quorum protocol (though Paxos-derived if you look at it the right way).” – Post by Marc Brooker in X ↩︎

For a detailed discussion on the trade-offs of leader-based consensus algorithms like Raft, see Alex Miller’s talk Enough With All The Raft. For insights on when consensus algorithms should be used, refer to Adam Prout’s article Categorizing How Distributed Databases Utilize Consensus Algorithms. ↩︎

Robbert van Renesse and Fred B. Schneider. 2004. Chain replication for supporting high throughput and availability. In Proceedings of the 6th conference on Symposium on Operating Systems Design & Implementation - Volume 6 (OSDI'04). USENIX Association, USA, 7. (usenix.org) ↩︎

Jeff Terrace and Michael J. Freedman. 2009. Object storage on CRAQ: high-throughput chain replication for read-mostly workloads. In Proceedings of the 2009 conference on USENIX Annual technical conference (USENIX'09). USENIX Association, USA, 11. (usenix.org) ↩︎

In Alex Miller’s article Data Replication Design Spectrum, protocols like Chain Replication are classified as requiring reconfiguration upon replica failures (failure detection / reconfiguration). The article also discusses variants of Chain Replication. ↩︎

Mahesh Balakrishnan, Jason Flinn, Chen Shen, Mihir Dharamshi, Ahmed Jafri, Xiao Shi, Santosh Ghosh, Hazem Hassan, Aaryaman Sagar, Rhed Shi, Jingming Liu, Filip Gruszczynski, Xianan Zhang, Huy Hoang, Ahmed Yossef, Francois Richard, and Yee Jiun Song. 2020. Virtual consensus in delos. In Proceedings of the 14th USENIX Conference on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI'20). USENIX Association, USA, Article 35, 617–632. (usenix.org) ↩︎

For more details on Virtual Consensus, see the paper as well as Murat Demirbas’s article Virtual Consensus in Delos and Jack Vanlightly’s article An Introduction to Virtual Consensus in Delos. ↩︎

See “Linearizability and quorums” in Designing Data-Intensive Applications. ↩︎

See the DynamoDB global tables talk by Jeff Duffy and Somu Perianayagam at AWS re:Invent 2024, from 42:11 onward. ↩︎

See “Implementing linearizable storage using total order broadcast” in Designing Data-Intensive Applications. ↩︎

“The internal transaction log replication protocol is modelled and verified using TLA+.” – Amazon MemoryDB: A Fast and Durable Memory-First Cloud Database ↩︎

Constantin Enea, Dimitra Giannakopoulou, Michalis Kokologiannakis, and Rupak Majumdar. 2024. Model Checking Distributed Protocols in Must. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 8, OOPSLA2, Article 338 (October 2024), 28 pages. (doi), (amazon.science) ↩︎

Mike Burrows. 2006. The Chubby lock service for loosely-coupled distributed systems. In Proceedings of the 7th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation - Volume 7 (OSDI ‘06). USENIX Association, USA, 24. (google.com) ↩︎

Mahesh Balakrishnan. 2024. Taming Consensus in the Wild (with the Shared Log Abstraction). SIGOPS Oper. Syst. Rev. 58, 1 (June 2024), 1–6. (doi) ↩︎

For more on Shared Log Abstraction, see the paper and the article by Murat Demirbas, Taming Consensus in the Wild (with the Shared Log Abstraction). ↩︎