Consistency Guarantees in Distributed Cache at Meta

Japanese version: Meta における分散キャッシュの一貫性保証

This article is based on Meta’s paper Skybridge: Bounded Staleness for Distributed Caches presented at OSDI 25. I came across it through Murat Demirbas’s blog post ATC/OSDI’25 Technical Sessions.

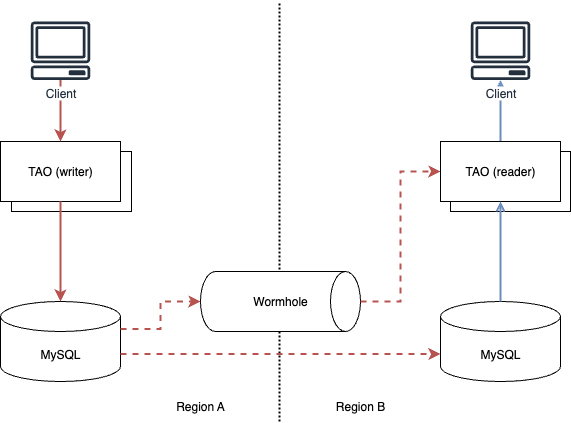

Meta maintains an in-house graph database called TAO for managing social graphs. TAO operates as a read-through and write-through cache with MySQL as its backend, supporting queries for edges and nodes. It is deployed across multiple regions worldwide, with the stored data replicated to replicas (both cache and MySQL) in each region.

Data replication between regions is performed asynchronously. Consequently, TAO’s replicas only guarantee eventual consistency, except when users directly access their own data. This necessitated developers to implement retry mechanisms and distributed locks to fetch up-to-date data, causing additional complexity and failures.

The issue of eventual consistency stems from uncertainty about when written data becomes readable. To address this, a new component called Skybridge was introduced to ensure that data can be reliably read with sufficient probability at least 2 seconds after it is written.

Cross-region replication inherently involves latency considerations. The standard approaches are either to employ consensus algorithms like Raft to guarantee strong consistency (though requiring a minimum of three replicas) or to use asynchronous replication (which only provides eventual consistency guarantees). Skybridge adopts a method leaning toward the latter while attempting to establish quantitative criteria for eventual consistency guarantees.

Cross-Region Replication

In TAO, data replication across different regions is handled by Wormhole, an in-house Pub-Sub system similar to Apache Kafka. It ensures that updates to primary MySQL shards in one region are propagated to TAO caches in other regions. During this process, Wormhole maintains update ordering (in-order) using at-least once semantics for message delivery.

Meta’s MySQL system, in addition to replicating data changes, periodically sends heartbeat messages to replication destinations every 500 milliseconds. These heartbeats contain timestamp information that can serve as a watermark to record the point to which replication has progressed.

Evolution of Consistency Levels at Meta

TAO originally ensured read-your-writes (RYW) consistency by routing user requests to specific cache servers. However, if requests were routed to different servers for some reason or if caches were dropped before replication completed, users might see stale data. Additionally, the static request routing for individual users presented scalability and availability challenges.

The solution to address these issues was introduced in 2016 with FlightTracker. FlightTracker manages metadata for user writes as tickets, ensuring that read operations retrieve data corresponding to those tickets, thus guaranteeing RYW for each user.

However, FlightTracker does not provide strong consistency guarantees for requests across multiple users. For example, when Alice invites Bob to join a chat group, Bob cannot recognize his group membership until replication completes.

Skybridge was introduced to handle such cases, allowing Bob to read writes made by another user (Alice) after a specified time has elapsed. This consistency level is known as bounded staleness and is supported by Azure CosmosDB and Spanner.

I was struck by how Facebook (then still known as Meta) had decisively abandoned consistency guarantees for cross-user requests when the FlightTracker paper was published in 2020. Based on their lack of consistency guarantees at Facebook scale, I have made a similar decision for products I was involved in. Ultimately, though, handling eventual consistency proves to be too challenging in practice.

Bounded Staleness

In addition to maintaining the existing RYW guarantees, Skybridge ensures that requests originating from different regions can retrieve data that is at least 2 seconds old. This 2-second threshold was carefully selected to allow Wormhole to complete replication in most cases while remaining acceptable from usability perspectives.

In practice, achieving 100% 2-second bounded staleness is inherently impossible. Therefore, Skybridge’s primary objective is to mitigate consistency loss caused by temporary replication delays in Wormhole and thereby improve the consistency level. Through actual implementation, Skybridge enabled TAO to achieve 99.99998% consistency when data is read 2 seconds after write operations.

Determining Staleness Without Skybridge

Even without Skybridge, we can still determine whether a cache entry is up-to-date (non-stale) by using the heartbeat mechanism described earlier.

Let $S$ represent the bounded staleness threshold (e.g., 2 seconds), $HLC_\mathrm{wm}$ denote the timestamp (watermark) of the heartbeat message sent from the replication source, and $HLC_\mathrm{item}$ indicate the time when the item was cached. HLC stands for hybrid-logical clock, which combines both physical time and logical time to ensure monotonicity. It can be compared with the current time $\mathrm{Time}_\mathrm{now}$. Additionally, let $\epsilon$ represent the maximum allowed error in time synchronization, typically caused by NTP [^1], with a practical value of 50ms.

The cached item is considered up-to-date if the following inequality holds:

$$ \mathrm{Time}_\mathrm{now} - (S - \epsilon) < \max(HLC_\mathrm{wm}, HLC_\mathrm{item}). $$

The right-hand side represents the most up-to-date time at which updates to the cached item ceased at the replication destination. Notably, when $HLC_\mathrm{wm}$ is greater than $HLC_\mathrm{item}$, it indicates that the cache has been inactive and no updates have occurred since at least the time marked by $HLC_\mathrm{wm}$. If the left side is less than $\mathrm{Time}_\mathrm{now} - S$, it implies potential replication lag where the cache updates have not yet been reflected. Furthermore, the equation incorporates the time synchronization error $\epsilon$ to make the determination more stringent.

A critical limitation of this determination method is that it cannot distinguish between a cached item being stale (missing the latest value) versus simply being inactive. When replication lag occurs, all items within a shard may be incorrectly marked as stale regardless of whether their caches have been updated.

Determining Staleness Using Skybridge

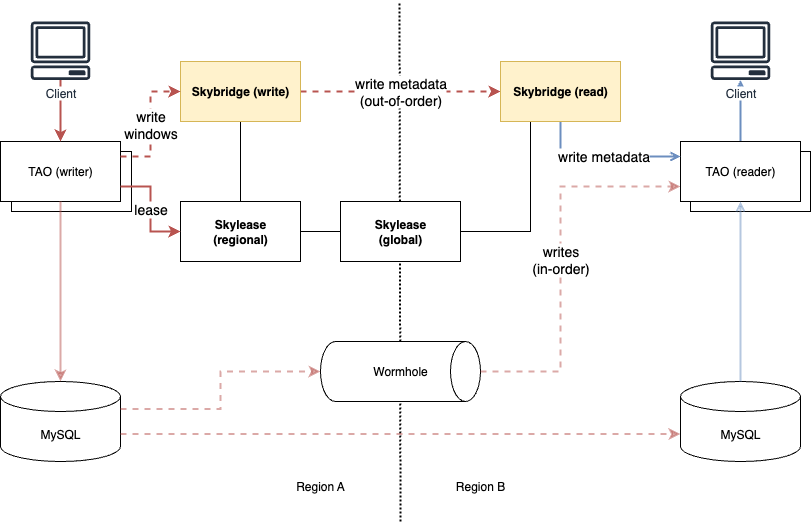

To address these limitations, Skybridge introduces an additional replication path specifically for providing data update timestamps, complementing the existing replication mechanism (Wormhole) used for ingesting data to caches. This enables TAO shards to verify the freshness of cached data. Unlike Wormhole, which guarantees both order and durability, Skybridge’s replication operates out of order and tolerates data loss to mitigate replication latency.

The Skybridge system consists of three primary components:

- Skybridge (write): Collects the timestamp at which data is written to TAO’s primary database.

- Replication Layer: Transmits data write timestamps to remote regions.

- Skybridge (read): Provides data write timestamps for determining cache freshness.

Skybridge (write) collects write timestamps of data in MySQL shards under TAO writers and forwards them to the replication layer in the form of write windows. To manage which TAO writer is responsible for which MySQL shard, each TAO writer registers a lease with a component called Skylease. Skybridge utilizes these leases to detect any failures (gaps) in timestamp replication.

The replication layer forwards each cache key along with its corresponding write timestamp (write metadata) to Skybridge (read). This transfer operates on a pull-based mechanism: Skybridge (read) initiates requests to Skybridge (write) to retrieve write metadata. This design allows Skybridge (read) to prioritize fetching the most recent write metadata and to fetch data from other sources in case of failures.

Skybridge (read) indexes the retrieved write metadata and provides it to the TAO read tier. The TAO read tier then verifies whether the cached data is stale through the following three-step process:

- Watermark-based determination similar to staleness detection without Skybridge

- Pre-fetched Bloom filter determination obtained from Skybridge (read)

- Direct retrieval of cache key write timestamps from Skybridge (read)

If the verification confirms the cache is up-to-date, it returns the cached value immediately. If the cache is determined to be stale or if replication gaps prevent determination, it fetches the latest value from upstream sources to refill the cache.

The size of write metadata index that Skybridge (read) can maintain depends on available memory capacity, typically allowing retention of metadata for a period on the order of minutes. Additionally, when replication lag is particularly significant for specific shards, the retention period can be temporarily extended.

Availability and Performance

Skybridge was implemented with minimal impact on the availability and performance of existing systems.

When write traffic to TAO spikes, it may become blocked while attempting to acquire leases from Skylease. To mitigate this issue, rate limits and circuit breakers have been implemented for lease acquisition, allowing writes to proceed without leases. Similarly, read operations undergo rate limits for fetching write timestamps from Skybridge; when these limits are exceeded, the system returns data regardless of cache freshness.

These strategies employ a fail-open approach. Under normal conditions, Skybridge prioritizes availability and performance over consistency when the system is unstable. However, in scenarios where consistency must be guaranteed, clients can set specific flags on TAO requests to cause requests to fail when bounded staleness cannot be maintained (fail-closed).

Summary

This article introduced Skybridge, a component implemented by Meta to enhance cache consistency across multiple regions. The solution addresses consistency guarantee challenges caused by in-order cache ingestion by introducing a separate out-of-order replication path that propagates write timestamps.

To detect write timestamp loss, lease mechanisms and their management component (Skylease) must be implemented. This introduces concerns such as increased system complexity and the need to carefully address potential impacts on availability and performance.

The concept of “guaranteeing consistency within S seconds” shares similarities with Freshness Service Level Objectives (SLOs). While Skybridge inherently involves trade-offs between freshness, availability, and performance, determining appropriate operational policies appears challenging—yet also presents an interesting area for further exploration.